Deconstructing John Scofield's Outside Lines: Chromatic Displacement & Functional Resolution

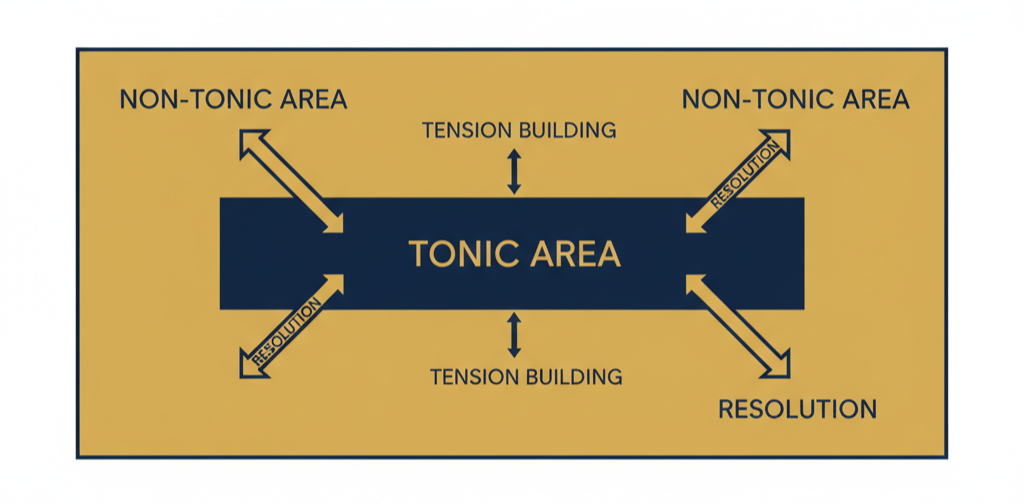

The 'outside' playing of a master like John Scofield is often misunderstood. It's not a random spray of dissonant notes but rather an artful and calculated act of 'Chromatic Displacement' followed by a 'Functional Resolution.' This advanced concept goes beyond simply shifting a scale up a half-step; it involves temporarily moving an entire harmonic structure into a non-tonic space before flawlessly returning it to the gravitational pull of the tonic center. Understanding this approach liberates you from the confines of scales and chords, allowing you to architect the narrative of tension and release in your improvisation.

Functional Harmony: Tonic Vs Non-Tonic

The Scofield-esque outside line is most effective at the structural turning points of a song's form. For example, in a D minor blues, the fourth bar (Dm7) is a critical junction that anticipates the functional shift to the subdominant G7 in the fifth bar. While many players might preemptively play lines from a G Mixolydian scale here to create a smooth transition, Scofield's approach is more audacious. In that fourth bar, he might deliberately play a structure from a half-step above the target, such as an Eb minor pentatonic scale or an Abmaj7 arpeggio—ideas that seem harmonically unrelated to G7. This is Chromatic Displacement: taking the entire melodic/harmonic structure you might have played over G7 and shifting it up to Ab7. This move creates intense tension, pulling the listener away from the established tonal center. However, what prevents this from becoming noise is the masterful 'Functional Resolution.' Scofield meticulously designs his lines so that the final note of the daring outside phrase resolves smoothly by half-step into a crucial chord tone of the target chord (G7)—most often the 3rd (B) or the 7th (F).

In essence, the journey out is bold and unpredictable, but the path back strictly adheres to the principles of strong voice leading. If your Eb minor pentatonic line in bar four ends on a Db, it resolves a whole step to the 5th (D) of G7, which is a weak resolution. But if it ends on Gb (F#), it can resolve by a half-step down to the 7th (F) of G7, creating a powerful sense of arrival. Therefore, the key to crafting effective outside lines is not to think about where you’re going, but rather to first design how you will get back. Once you master this principle, you can apply it to more complex structures like upper-structure triads for even richer harmonic textures.

Just as we learn to understand modes as shades of emotional color and chords as points in a functional flow, we must see outside playing as a tool for designing the emotion of tension. Instead of focusing on getting 'out,' design your exit strategy first. Before you play an outside line, ask yourself: "Does the last note of this phrase have a clear path back to the 3rd or 7th of the next chord?" This discipline is what separates controlled, exciting chaos from mere noise. It is the true aesthetic of advanced jazz guitar improvisation.