Deconstructing Harmony: A Functional Analysis of 'Blue Bossa' with Upper-Structure Triads

The Secret to Creating Complex Sounds Over Simple Chords When listening to a masterful jazz performance, a common question arises: the chord chart clearly says "Cm7 - Fm7," so why does their playing sound so much richer and more modern than mine? The secret often lies in a sophisticated concept: Upper-Structure Triads (USTs). This technique goes beyond merely adding tensions; it involves functionally reinterpreting the harmony, allowing the improviser to superimpose new chords over the existing ones. This grants immense freedom in both soloing and comping. Today, we'll delve into the world of upper structures, using the chord progression of the jazz standard "Blue Bossa" as our guide.

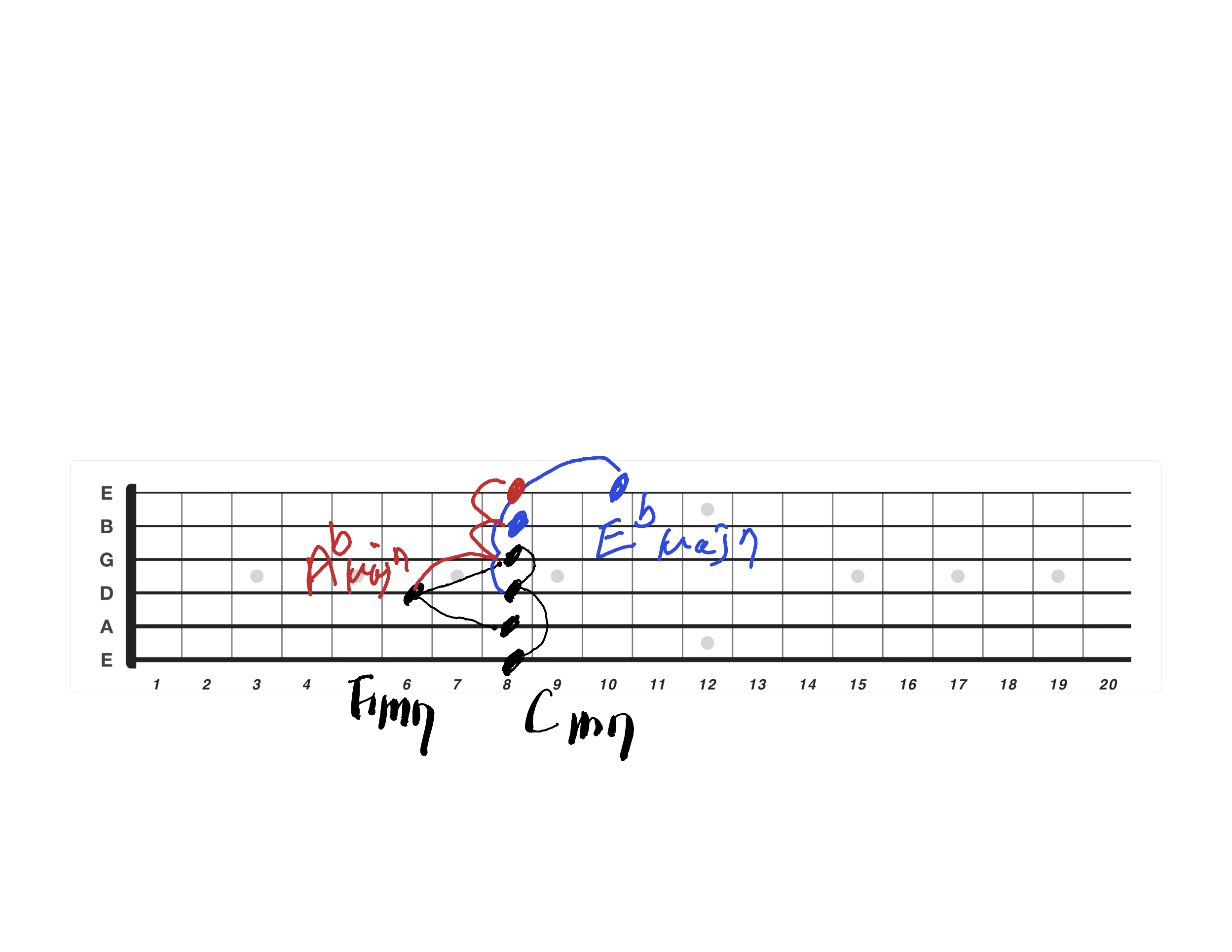

Uppstructure of Cm7, Fm7

Deconstruct the Chord, Play the Superstructure The core idea of using upper structures is to assume that the foundational harmony (the root, 3rd, and 7th) is being handled by the bass player or the lower register of the piano. The guitarist is then free to focus on playing the "superstructure"—a new chord, often a simple triad or seventh chord, built from the upper extensions (9, 11, 13) of the original chord. This mental shift enables far more concise and logical voice leading on the fretboard. Let's analyze the first two bars of "Blue Bossa": Cm7 – Fm7.

Over the Cm7: If we mentally remove the root 'C', we are left with the notes Eb, G, and Bb. By adding upper extensions like the 9th (D), we can form new harmonic structures. A very effective choice is to think of an Ebmaj7 arpeggio or chord (Eb, G, Bb, D). Playing Ebmaj7 over a C bass note powerfully implies a rich Cm9 sound.

Over the Fm7: Similarly, we can use an Ab Major 7 chord (Ab, C, Eb, G) as the upper structure for Fm7. The notes of AbM7 perfectly outline the sound of an Fm9 chord. Here is where the magic happens. To get from Cm7 to Fm7, an advanced player might think of moving from Ebmaj7 to AbM7. On the guitar neck, these two voicings are located very close to each other. The transition requires only a few notes to move by a half-step. Instead of making a large jump to find the new root 'F', the harmony shifts elegantly through the subtle movement of the upper structures. Now, let's look at the climactic II-V-I progression in the tune: Dm7b5 – G7 – Cm6. 1.

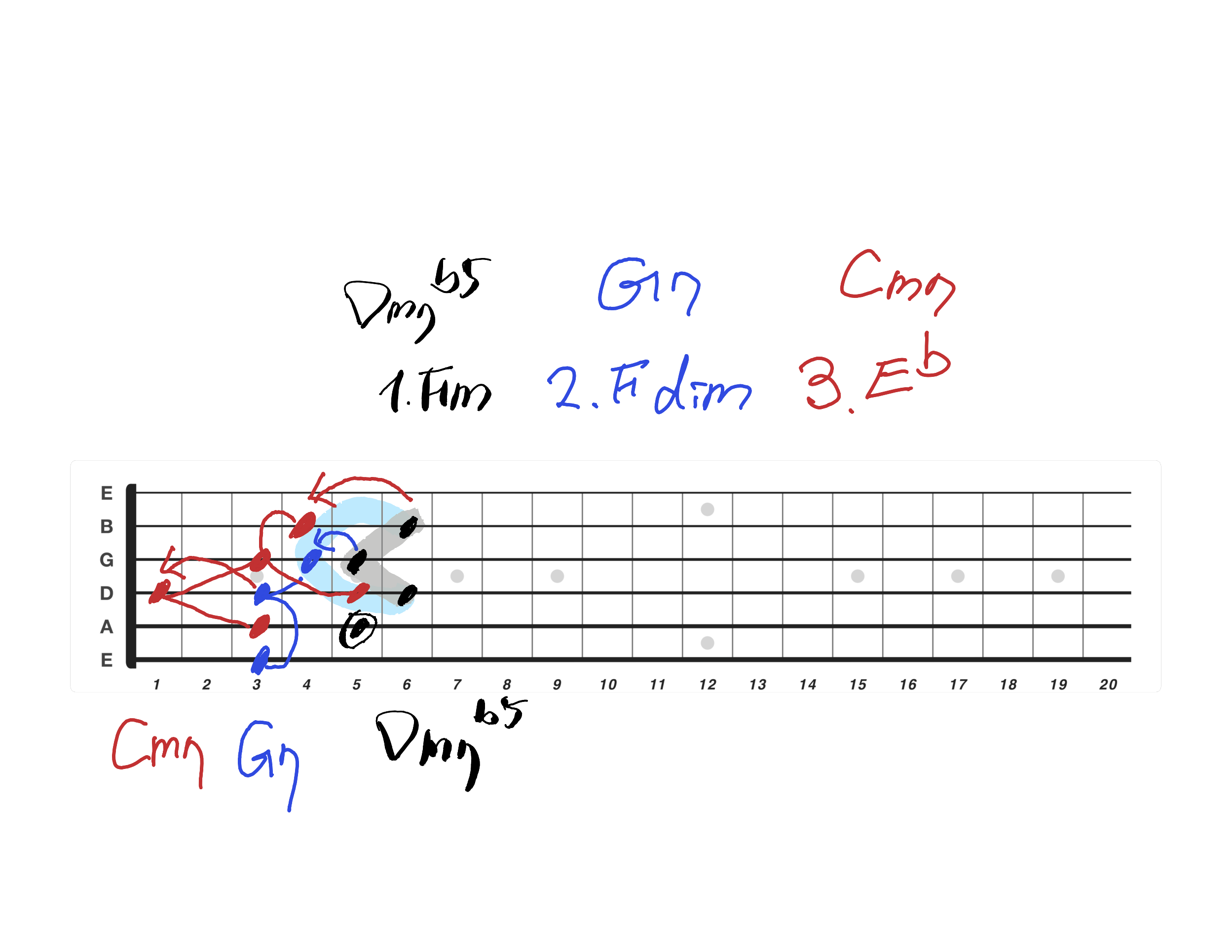

Over Dm7b5: If we remove the root 'D', the remaining notes (F, Ab, C) form a perfect F minor triad. While the Dm7b5 chord is sounding, we can improvise using lines derived from F minor. 2.

Over G7 (Altered): For a modern, altered dominant sound, we can create a smooth transition from the previous F minor triad. By simply moving one note, C, to B, we get notes that strongly suggest an F diminish sound or, more accurately, the key altered tensions of G7: the b9 (Ab), 3 (B), and b7 (F). For voice leading purposes, one can often think of this as moving from an F minor sound to an F diminish sound.

Over Cm6: The tension of the G7alt chord can then resolve beautifully back to the stable sound of our C minor tonic, which, as we established, can be represented by the Eb upper structure. The result is a complete re-framing of the progression. The harmonically dense journey of Dm7b5 → G7 → Cm6 is transformed on the fretboard into a highly logical and minimal movement of triads and small structures: [Fm → F diminish → Eb]. This is the thought process of a musician who understands harmony functionally and seeks the most efficient and musical path on their instrument.

Uppstructure Triad of Dm7b5-G7(b9)-Cm6

Jazz Becomes Simpler When You Understand Harmony as Color Upper-structure theory isn't just an abstract academic exercise; it's a powerful tool for re-organizing complex jazz harmony into intuitive, playable units (often simple triads) on the guitar. When you stop seeing chords as individual passwords to be memorized and start understanding their function and their brilliant superstructures, your improvisation will gain both unpredictable freedom and sophisticated logic. Start applying this concept to your playing, and listen as the depth of your sound expands exponentially.

For more insights into advanced jazz harmony, including upper structures and modal theory, visit Bridge: Theory and Sound.